It Depends

I remember early in my career when saying “it depends” was considered obnoxious.

It was something you often heard from consultants or contractors, usually when they wanted to avoid giving a real answer. At the time, it was used as a way to dodge details instead of explaining the thinking.

And now here I am, saying it.

The difference is I’m not using “it depends” to end the conversation. I’m using it because real data work actually does depend on context, constraints, timing, and tradeoffs.

The important part isn’t that it depends. It’s understanding what it depends on and why. And being clear about that doesn’t remove accountability. A decision still has to be made. Someone still owns the call.

As humans, we’re wired to look for simplicity.

We like yes or no. Good or bad. Right or wrong. Clear answers help us move faster and feel more certain. Our brains are constantly trying to reduce complexity because uncertainty is uncomfortable and mentally expensive. It’s just how we make decisions and make sense of the world.

The problem is that data work doesn’t cooperate with binary thinking.

I’ve been seeing a lot of posts and comments lately saying that everyone in data should focus solely on outcomes. It sounds decisive. Actionable. Comforting, even.

It’s not wrong. It’s just when taken literally, it’s incomplete.

Real data work is rarely a clean, either/or choice. Outcomes matter, of course, but not at the expense of foundations. When we focus only on outcomes, we tend to build point solutions for singular problems. They work, sometimes even impressively well, until the next question shows up, or the next team, or the next initiative.

Foundations almost never look like outcomes in the short term. Data models, governance, semantics, reliability, platform choices - none of these come with a neat KPI attached. But they’re the reason you can deliver outcomes repeatedly, and faster over time.

Saying “it depends” can feel unsatisfying, or like a cop-out, because our brains want closure. Simple rules help us feel oriented. Tradeoffs don’t.

Data ecosystems, though, are built entirely on tradeoffs: between speed and stability, flexibility and control, short-term wins and long-term health.

The issue usually isn’t bad intent. It’s not that people don’t care or don’t understand data. It’s that reality is messy, and messy is hard to talk about.

Organizations are messy. Legacy exists. Constraints exist. People exist with history, incentives, habits, and opinions.

Advice optimized for conference talks, blog posts, or LinkedIn often collapses under this mess. Evangelism tends to optimize for clarity. Operating environments demand correctness.

The Fitness Analogy

Lately, I’ve been learning a lot about fitness for longevity.

As a woman of a certain age, the old fitness advice starts to fall apart. “Just go for a walk”. “Just eat less”. “Just do what you’ve always done”. That kind of guidance used to be sufficient. But not anymore.

Not because walking or diet don’t matter, they do, but because at some point the system gets more complex. Hormones change. Recovery changes. Muscle matters more. Bone density matters. Sleep matters. Stress matters. What worked before eventually stops working, even if it feels counterintuitive to admit.

Diet is a good example. There’s a big difference between eating less and eating better. Eating less can give you fast, visible results. The scale moves. Clothes fit differently. On the surface, you look great.

But that doesn’t mean it’s healthy or sustainable. You can lose weight at the expense of muscle and bone. On the outside, everything looks fine. Underneath, your body is actually getting weaker and your longevity gets worse.

Do you see the parallels to data? I do.

I was listening to a podcast recently about fitness and longevity when the host asked an expert what the must-do workouts were if you only had three hours a week. The expert struggled to answer this question. It was not because she didn’t know the science, but because reducing something complex to one or two “musts” ignores how systems actually work.

Strength matters. Cardio matters. Mobility matters. Recovery matters. Over-optimize for one, and something else quietly suffers.

Data works the same way.

We want a single answer because it feels actionable. But systems don’t behave that way, no matter how much we wish they would.

Outcomes vs. Foundations Isn’t a Real Choice

“Focus on outcomes” is good advice. “Build solid foundations” is good advice. “Modernize your tools and methods” is also good advice.

The mistake is treating any of these as mutually exclusive.

The work has to start with a real business problem. Not an abstract capability. Not a platform for the sake of a platform. Something concrete that actually matters to the business.

But solving the problem shouldn’t mean ignoring the foundation or the reality of the tools and methods you’re building on.

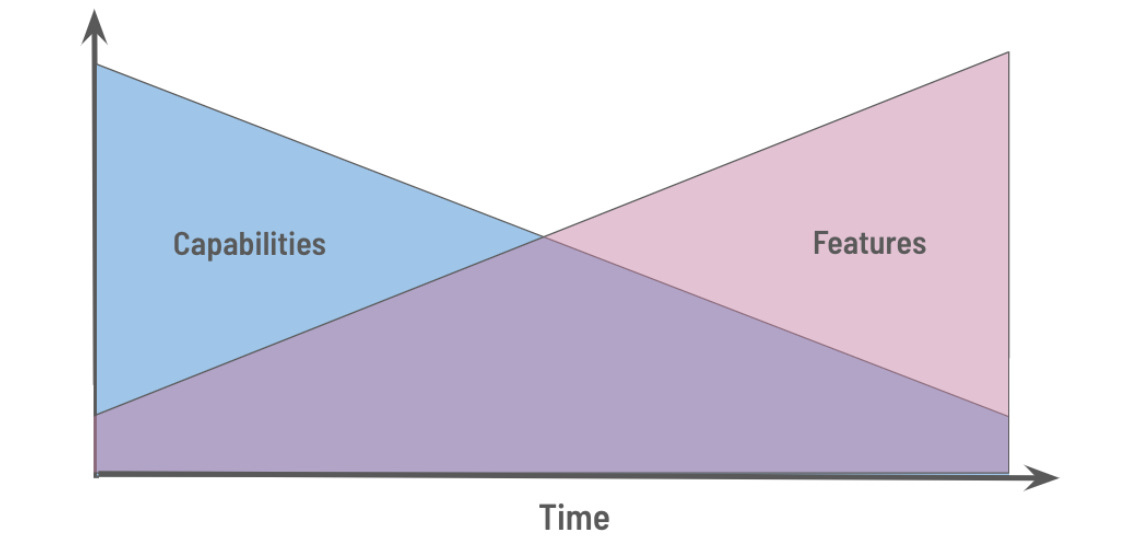

I think about this as capabilities versus features over time. Early feature work often delivers visible wins. Dashboards ship. Pipelines go live. Use cases get checked off. That progress is real, and it matters.

What’s easier to miss is what determines whether those wins compound or stall.

That’s where capabilities come in as shared infrastructure, data models, standards, tooling, patterns, and ways of working. Capability work rarely shows up as an existing feature. It’s quieter. Slower. Harder to demo. And because of that, it’s also the work that’s easiest to defer “just for now.”

This chart shows how effort and value shift over time.

Early on, most effort goes into building capabilities. That work is heavy upfront and often invisible, but it’s what makes anything else possible.

As those capabilities mature, features start to roll out faster and with less friction. More of the visible value comes from features not because foundations stopped mattering, but because they already exist underneath.

The overlap is the key part. Capabilities never disappear, and features don’t magically wait their turn. Teams are always doing both. When the balance is right, features get easier to deliver over time. When it’s not, every new feature feels harder than the last.

This is also how technical and methodological debt sneaks up on you. Not all at once. Not because anyone made one bad decision. But because capability work keeps getting pushed out in favor of the next visible win.

A good red flag to watch for: If every new feature feels harder, slower, or riskier than the previous one, you’re probably paying for capabilities you didn’t invest in earlier. From a leadership perspective, another signal is when delivery slows even as headcount, tooling, or process increases. This is a sign that complexity is compounding faster than capability.

The real work, and the harder work, is knowing when to lean into speed and when to invest in structure.

Speed is sometimes exactly what’s needed. Urgency is real. But speed without an explicit understanding of long-term cost is how teams accidentally optimize themselves into corners.

Some decisions optimize for this quarter. Some optimize for this year. Others are about not boxing yourself in three or five years from now. Most tension shows up when decisions optimized for one time horizon are later judged by another.

So when someone says “just focus on outcomes,” or “just build foundations,” or “just modernize everything,” my answer is usually the same.

It depends.

And what it depends on is where you are in time, what capabilities already exist, and what future you’re optimizing for.

It Also Depends on Where You’re Sitting

There’s another dimension to all of this that doesn’t get talked about enough: perspective.

Data teams are some of the hardest-working people in the organization. From the IC seat, the pressure is real: move too fast and the system becomes fragile. From the leadership seat, the pressure is just as real: move too slowly and the business misses opportunities.

The uncomfortable truth is that the system often rewards both behaviors even when they hurt the whole. Leaders are rewarded for visible outcomes. ICs are rewarded for stability and correctness. Balancing the two is rarely what gets measured or celebrated.

Both perspectives are valid. Neither is complete.

This is where binary thinking really fails us. It’s not ICs versus leaders. It’s not speed versus quality.

This isn’t a misunderstanding. It’s a structural tension. Busy doesn’t always mean productive. Outcomes don’t always mean sustainable. Missed opportunities hurt the business just as much as brittle systems.

The teams that get unstuck aren’t the ones with the loudest evangelists, the cleanest slide decks, or most modern systems. They’re the ones where ICs and leaders start sharing perspective, not just priorities. Where ‘we need to slow down’ and ‘we can’t afford to slow down’ can both be true, and the conversation is about navigating that tension rather than resolving it. And navigating that tension isn’t about picking a side. It’s a shared responsibility.

A Practical Way to Think About It

Right now, I’m changing how I approach fitness and diet because I want to be strong enough to lift my carry-on into the overhead bin.

That’s the immediate problem I’m trying to solve.

I’m short. That means I need upper-body strength, core strength, and balance, because I’m usually doing it on my tiptoes. Walking more won’t solve that problem. Eating less won’t either. I need to train the right things, in the right way, for the outcome I care about.

The long-term benefit is that this kind of training also helps me stay active and self-sufficient well into my 90s, assuming I’m lucky enough to live that long. Strength I build for today compounds into resilience later.

That’s how I think about data work too.

Start with a real, concrete problem. Solve it deliberately. But solve it in a way that builds strength underneath, instead of quietly weakening the system.

If we want data platforms and data teams that are still strong years from now, we can’t optimize only for what looks good today. We have to invest in what keeps us stable, adaptable, and capable over time.

So the next time you hear advice that sounds like a silver bullet, pause and ask:

What problem am I actually trying to solve right now? And am I solving it in a way that makes the next problem easier or harder?

Because in data, just like in fitness, the goal isn’t quick but unsustainable wins. It’s longevity.

And yes … it depends.

Yes—incomplete thoughts. And time under tension.